Workshop: Seismic Vibrations + Cultural Noise

On 2024-05-19, at the occasion of the International Museum Day, EMAF ( where I exhibited at that time in the *Feelers, Sensors* group exhibition ) invited me to do a workshop that would accompany both my *Sleep Like Mountains* work and the group exhibition topic. I wanted to work a bit more with sounds of the Earth, so I came up with this workshop which I thought would be a lot of fun to prepare (which it did!!)

Seismic Vibrations & Cultural Noise

Earth is never static, always moving. So, naturally, Earth is a conductor (and constant generator) of low frequency pressure waves (sound). In this workshop, we will build our own seismic instruments to sense; feel those vibrations that traverse Earth’s surface. We can listen to “cultural noise” through Earth, see seismic activity in real time, or amplify this messy mix of earthy vibrations to make it tactile.

Conceptually, this workshop connects to a wider interest I have at the moment in working within the geo/physical/bio/techno/psycho/medial networks of Earth’s technological + natural environments. As a way of interfacing with Earth and self-immersion as a way of embedding and embodying within the more-than-human world, where Earth's spaces and landscapes are viewed as collaborative emergences (the space is being constructed by those non-human and human bodies/forces that reside in those space, and therefore create landscapes).

Also, I drew a lot of inspiration from eco-feminist land art (*Grass Breathing* by Ana Mendieta), psychogeophysics (*Psychogeophysics Walker* by Martin Howse), media art installations (*Studien zur Sehnsucht* by Kerstin Ergenzinger) and the short film told from the perspective of a mountain / monster residing in the mountain/water *detours while speaking of monsters* made by Deniz Şimşek + Mónica Martins Nunes (using a geophone!).

> Preparations

I found some nice resources online on how to DIY build your own geophone ( seismic, low frequency "microphone" ):

- https://www.instructables.com/DIY-Seismometer/

- https://www.instructables.com/Seismometer/

- https://forum.arduino.cc/t/arduino-geophone-application/182534

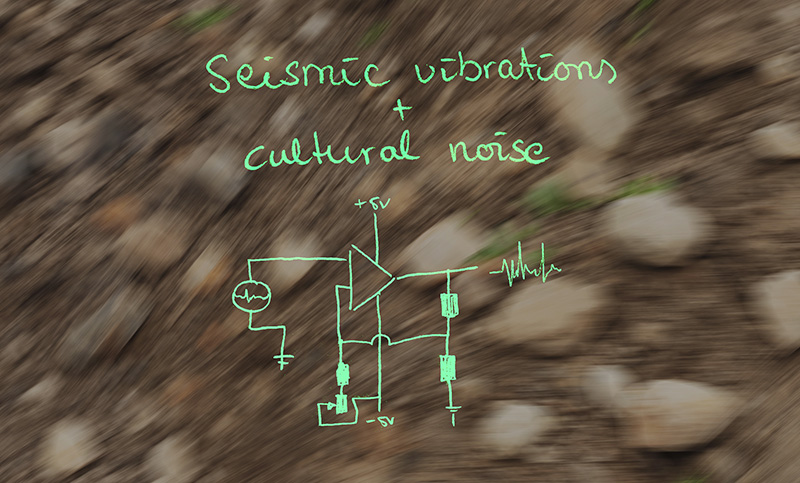

(includes nice schematics in the comments) - what's inside a geophone:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EaQ9cERXBf4 - a different DIY geophone design:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HcXWzV9wudM

In the end, I decided not for the audio-engineering-wise *purest*, but the cheapest option. Which still worked well enough to actually sense (= make tactile/audible) seismic vibrations. It was a bit noisy at first, but sounded quite nice with some filtering. So, here's what I prepared:

1) Using a professional geophone

At first I bought a "professional" geophone (Sensor SM-6 OB 15 Hz 3K6 Ohm Geophone) for around 50€ on Ebay, so I would have a reference of what my DIY geophone more or less should (?) sound like.

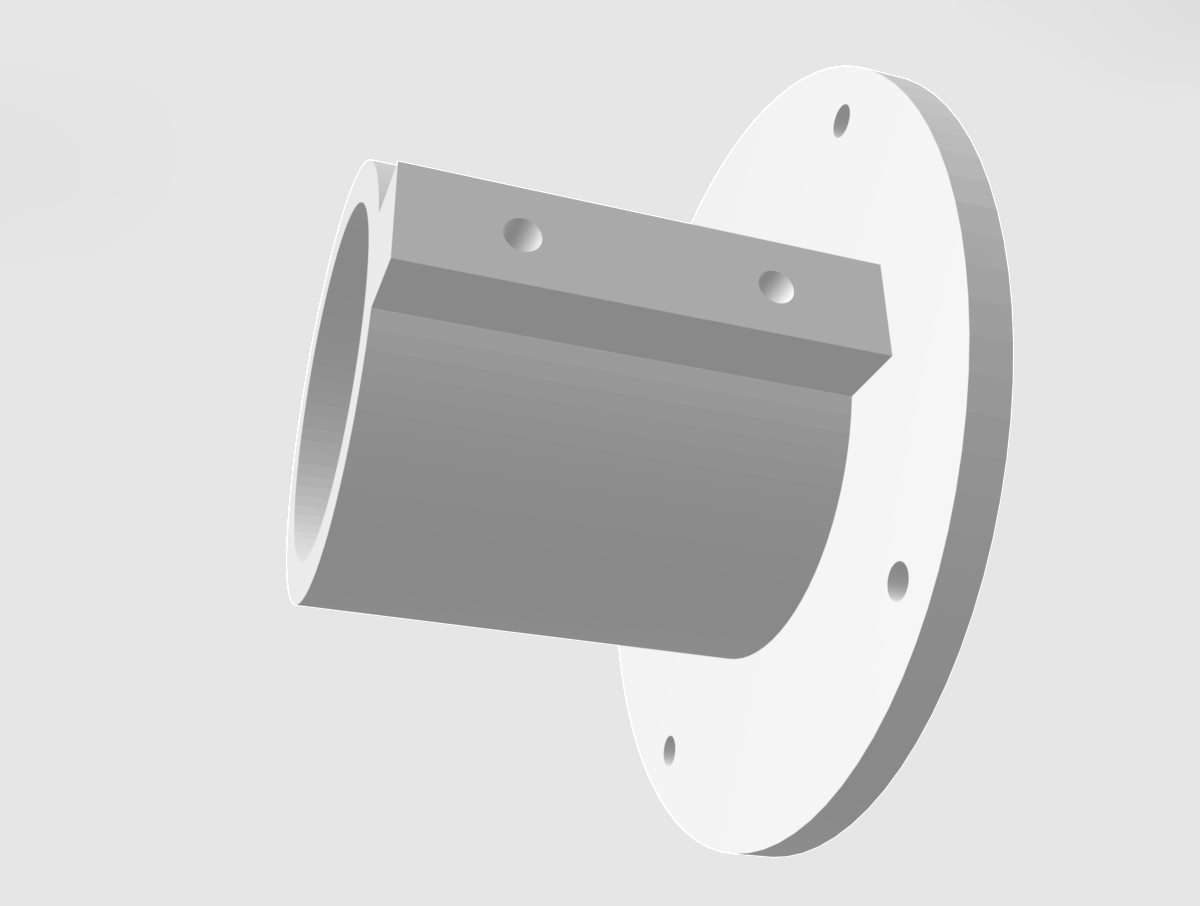

In OpenSCAD, I modelled a 3D-printable small case for it, so I can mount it on this sun shield thingy holder that my mom found:

I was thinking this would be a nice way to stick the geophone in the ground and listen to it, which it did, but unfortunately the fact that it's made from metal makes it have an echo and super intense resonance. Like you can hear in this demo:

The geophone has two cables soldered to its terminals that lead to a 3.5mm audio jack (mono). The audio jack is plugged into an audio interface (I use a zoom recorder here) and then further amplified + filtered in Ableton Live, but any adjustable analog/digital low pass filters + amplifiers would work here.

2) DIY geophone

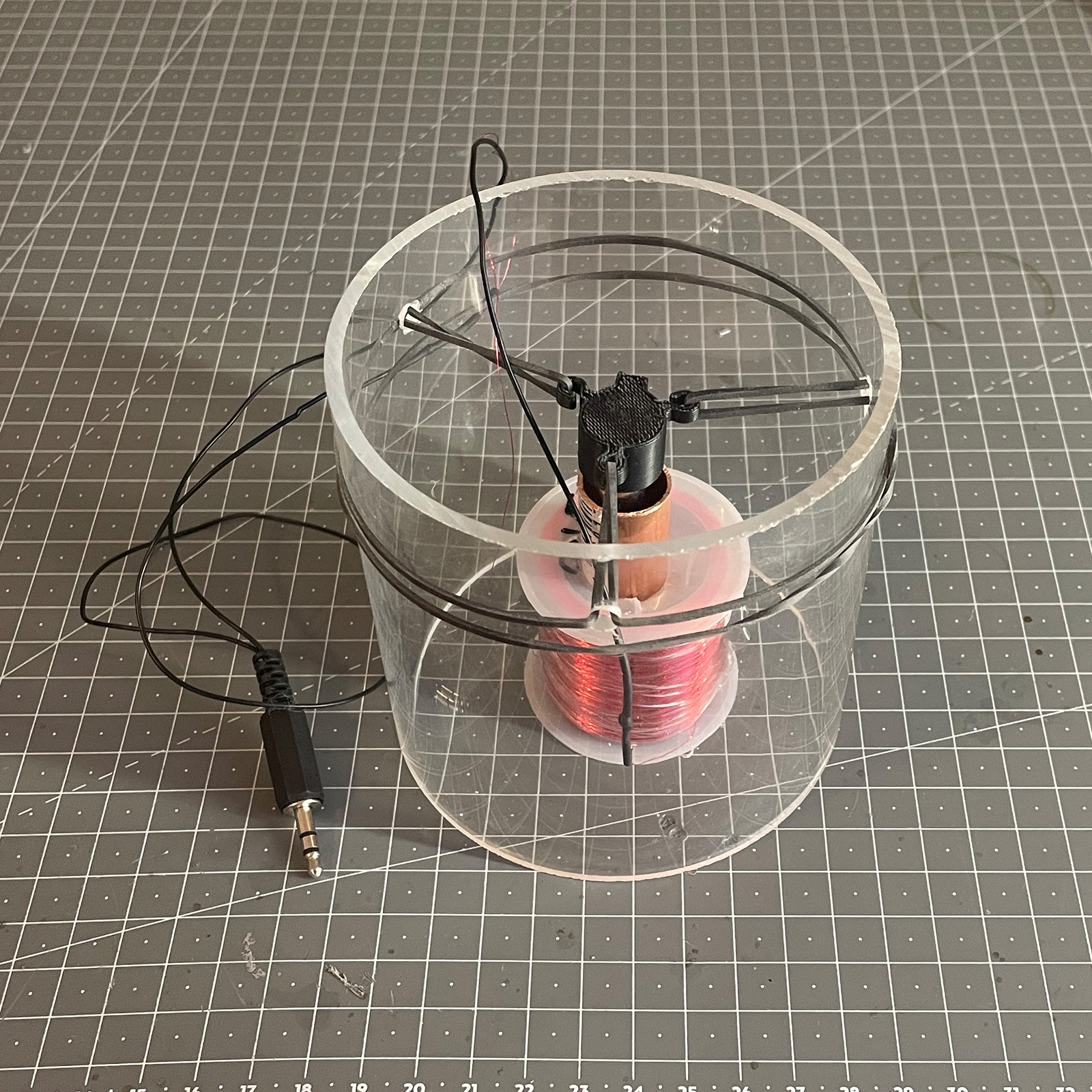

The basic idea of a geophone is either a wiggly coil around a static magnet to induce current, or the other way around. Then there also should be a dampening material, such as a copper tube, that will help the magnet stop wiggling sooner after the intial vibration has already passed. This is the design I came up with:

There is a big acrylic tube as a case (which I sourced very cheaply from https://hbholzmaus.de left over / scrap section). An elastic rubber band keeps the magnet holder in place that I modelled as well for 3D printing. A coil (0.15mm 600meters) is placed in the middle. The two ends of the coil are soldered each to a cable that leads to a 3.5mm audio jack. With a hole-enlarging drill bit I made a hole that is big enough for holding the copper tube. Then the magnet is fixed inside the magnet holder with a screw (or glued) and more or less awkwardly positioned in the copper tube. The big acrylic tube case keeps most of the wind out, so even though it looks very hacky, it actually worked quite nicely in the end. Ideally, you would put a lid on the top with a heavy weight on it, such as a brick or something. This way the pressure waves would propagate more easily through the material layers (ground -> acrylic case -> rubber band -> magnet inside the coil).

> Some workshop impressions :)